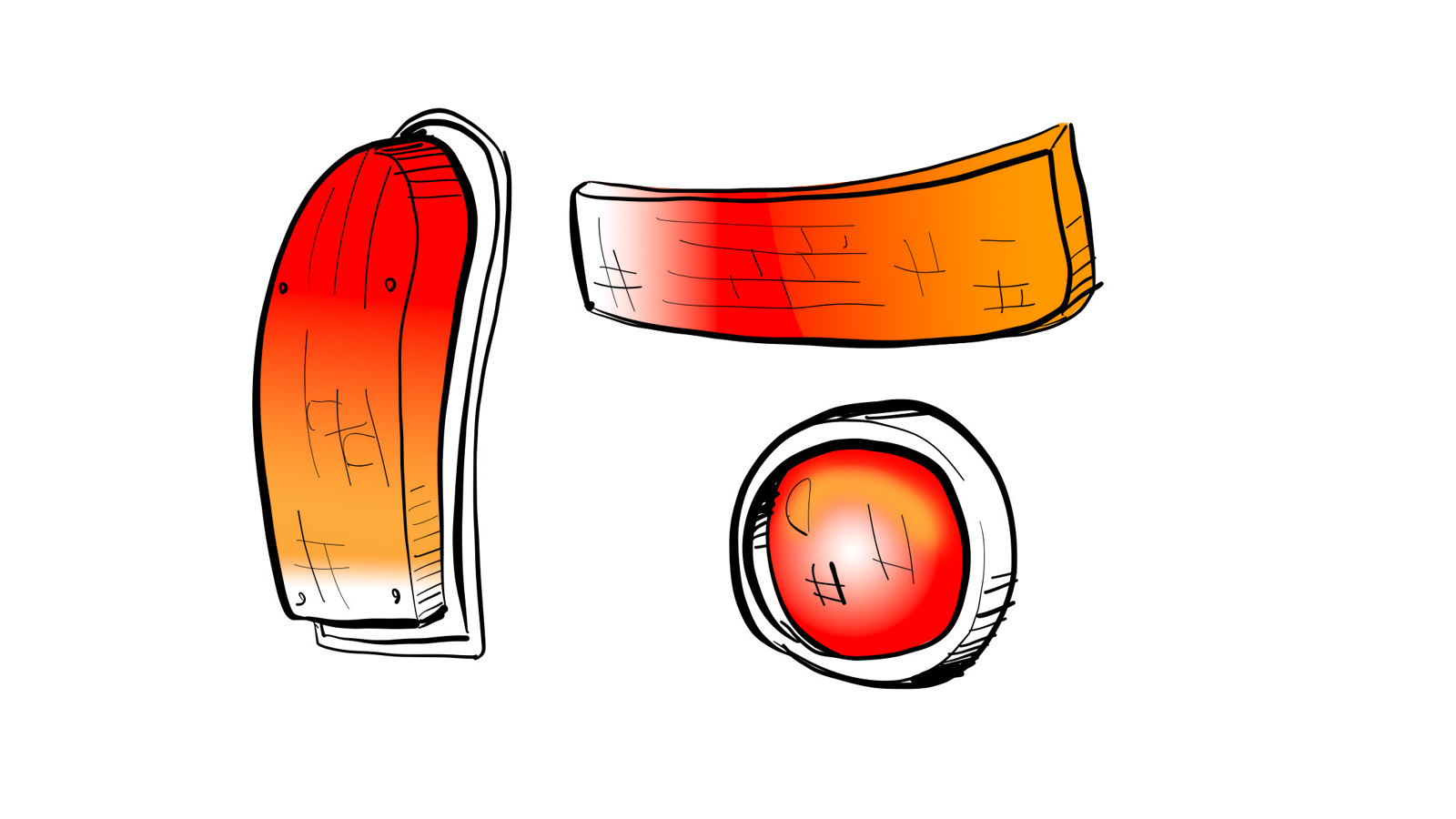

Sometimes called Gradient Taillights, these have taken on a near-mythical significance in the taillight community because, as far as anyone has been able to determine, they have never actually appeared on a production vehicle. While the actual design of such lights varies wildly, and many versions can be seen on votives and other ceremonial artifacts, the fundamental qualities of an Ombré Taillight are simple: the colors of the sections of the taillight must blend together in a smooth, unbroken gradient that includes amber, red, and clear.

See what I mean there? There’s no hard breaks between the various sections, just smooth transitions from color to color, a result that many in the Taillight Community consider to be the idealized form of the taillight, as the harmony between the multiple colors and the perceived unity despite differences is considered to represent an ideal, utopian world, a world where turns are always signaled, reverse travels are well lit with a pure alabaster light, and the rear of every car is conspicuous and vibrant. Plastic dyeing technology is capable of producing such an effect; cheap plastic water bottles, for example, have been produced with similar effects for years. The lack of gradient taillights isn’t an engineering issue; we have the technology. Regulation-wise, as long as certain criteria are met such as light output and each section of the taillight meeting the requirements for visible area (for example, a brake light needs to have 7.8 square inches of illuminated area), then there’s really nothing against regulations about this still-hypothetical design, as what’s between those required sections of lens is not specified. Has any car, production or otherwise, come close to the Ombré Taillight? The sad truth is not really. There’s a few examples that are close: the Nissan Pulsar NX’s diagonal-slash mask over a fairly conventional taillight gave a sort-of illusion of a gradient, kinda. Ford’s 1992 Focus concept car used an interesting scatter-dot taillight setup that sort of visually mixed the colors, but looked more biological than gradient, if we’re honest.

A number of carmakers in the early 2000s, such as Volkswagen, used an approach to taillights where a horizontal raster of red lines would serve to kind of obscure the amber turn indicator area, which did blend them together somewhat. It’s not exactly a gradient, either, but it’s something. The only car I can think of that I might qualify is the North American market Series 2 Jaguar XJ sedans. I’ve written about these taillights before, as they fascinate me so, being the only taillight that uses an exclusively amber lens:

In this unusual setup, it’s an all-amber outer lens over an inner red lens/bulb setup for the brake/taillamp. The end result is sort of a gradient, a radial gradient of sorts, centered on the red brake/tail inner lens and radiating outward to where it fades out into the amber of the rest of that gothic tombstone shape. It’s still not the ideal Ombré Taillight, but among the gradient-wishers in the Taillight Community, it’s the best they have in reality. Will advances in LED tech be what it takes to make the Ombré Taillight a mass-market, modern reality, finally? Will we have to wait for taillights made from full-color, 32-bit LCD displays before we’re treated to a glimpse of this vehicular lighting holy grail? Automotive lighting designers, take note. There’s a striking and unexpected opportunity just waiting for whomever is bold and daring enough to try it: the gradient taillights. It’s time. I kao remember Peugeot making a fuss about the tail lights in their phase 2 106 from 1996. It was the first car to have an all red tail light that incorporated amber turn signals and a white reversing light. It was all over the launch literature but unfortunately can find no trace now. But of course you’d know all this if you ever spend time in the trendy Le Feu Arrière situated in Barbès in Paris. In fact, the Renault 25 also had ribbed taillights, just don’t ask how I know. Many children first experience this with the red and yellow plastic circle lights on the classic school bus. The lights flash when children board and instantly the young minds are inundated with cherry and lemon candy thoughts or some variation thereof. Often, young children deprived of these candies have a stronger coefficient of visual representation. Jason’s current discovery of the Ombre (gradient) taillight expression fully supports this hypothesis but using the classic “blended” flavor approach. The cherry flavor melts into orange into lemon into coconut similarly generating a “Rocket Pop” (also called “Bomb Popsicle”) viewpoint. This often is found in much warmer climates for some apparent reason baffling researchers. In other words, it can basically summed up as simple “eye candy”. Therefore, I give you the ombré tail-lit Volvo YCC (your concept car) from 2004: https://www.media.volvocars.com/global/en-gb/media/photos/8277 987 Cayman Design Edition Taillight: https://i2.wp.com/cg-cars54.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/IMG_6254.jpg As someone with the aforementioned taillights, as well as a MK7 with the perfectly-designed MK7.5 Euro-spec sequential taillights swapped… keep these posts coming, Jason. Three words. Three words into the article and I’m alright shaking my head and muttering “Jesus Christ…” to myself. I think it’s called The Blinking Ambergris. I’ll show myself out. The SAAB 9-3 estate also had glazed rear lenses, so when each part lit up the same kind of gradient effect happened with a blurry separation between each colour. Such a snappy little guy from back in the days when it was okay to make cars whose main thing was being fun. It had it all – coupe, popup headlights, t-tops, and even that super-rare sportback wagon conversion. Miss those days. TIL two new words. The Autopian continues to improve literacy throughout the English speaking world.