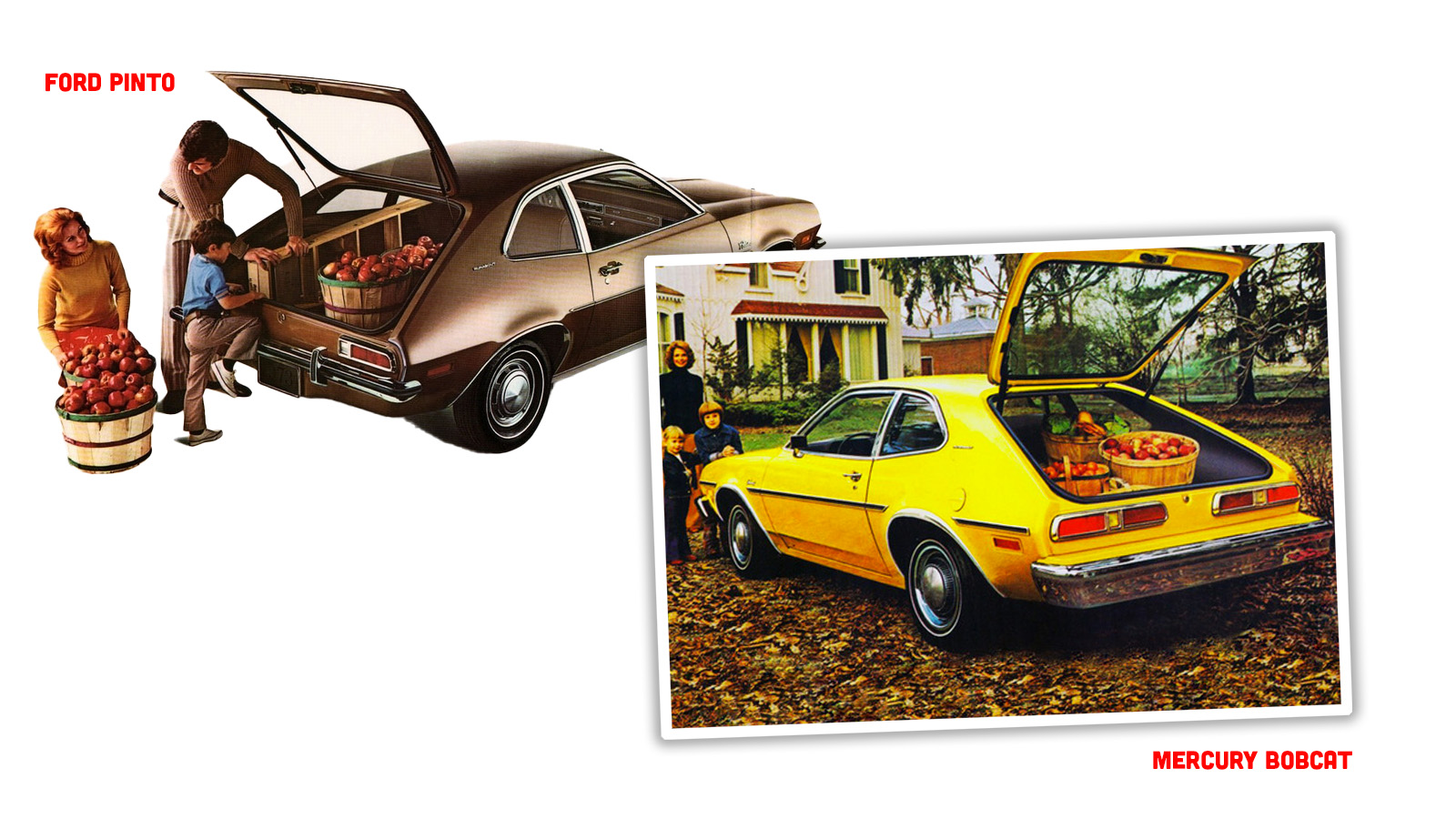

In keeping with the general theme of sucking, I think I’d like to pick a Mercury that many, many people would likely say sucks: the Mercury Bobcat. They’d likely say this because the Bobcat was a re-badged Ford Pinto, a car that’s best known for having a design flaw so egregious and dangerous, and the handling of it so callous and bungled that the whole thing is now tort law legend. And, sure, nobody is that crazy about fiery death, sure, but at the same time, the Pinto’s 2.2 liter inline four was a pretty great engine that went on to power all sorts of interesting cars, including the legendary Merkur XR4ti. And it wasn’t a bad design, really, I mean, other than the fuel tank situation. The Bobcat was Mercury’s first subcompact car, and I think what I find so interesting about the Bobcat is that it’s a sort of object lesson for the concept of what defined “premium” for a car in the 1970s. Mercury wasn’t Ford’s premium-premium brand, that was Lincoln, but it was a definite step up from Ford, and as a result, the car needed to convey this concept. Even better, the Bobcat is a lesson in what the minimum was that an automaker could get away with changing on a car to kick that particular car up a rung or two on the social ladder of automobiles. As a result, one could compare the Pinto and the Bobcat and learn a bit about the visual and other signifiers of automotive status in the 1970s, a subject that’s worthy of innumerable doctoral theses and long, long documentaries. So, let’s do just that:

Now we’re finally getting into the essence of what’s sorta-fancy is. The two cars share almost exactly the same body sheet metal, with one notable exception: the hood. The Mercury has a “domed” hood, and that’s not because it has to accommodate a larger engine – it doesn’t – but because the hood has to provide room for the most important single signifier of “class” in the American automotive lexicon: a tall, chromed grille. The Bobcat’s hood allowed for that taller grille with the fine vertical slats, a striking contrast from the Pinto’s low, wide grille. It’s a more archaic sort of look, really, but in this context, archaic means traditional, and tradition means class and money. Chrome also is a signifier of swank, so the headlight bezels are now chrome instead of body-colored, and the turn indicators have transformed from a quartet of rectangular windows on the Pinto into a pair of chrome-rimmed, almost lantern-like units, with lenses protected by a chrome cross for an almost nautical feel. Bumper guards are chrome instead of all rubber, the M E R C U R Y name is elegantly spelled out on the hood, and wedding-invitation-scripr badges that read Bobcat are placed on the front quarter panel, above a bit of extra chrome-and-rubber trim to both protect the doors from dings and provide another little visual reminder that you had a bit more cash to throw around than your average Pinto-punter.

Around the rear, your status was primarily conveyed via the wider taillights of the Bobcat, which were seemingly made by chopping off the red section of the basic Pinto/Maverick taillights, flipping them left to right, and tacking them on at the other side of the reverse lamp. The result was much bigger taillights, which is another one of the American Lexicon Of Class’ visual signifiers.

On the inside, the primary way American carmakers in the 1970s telegraphed the idea that you, the car’s owner, were worth a damn was by surrounding you with fake wood, the automaker equivalent of giving you one of those quick upward nods of acknowledgement and respect. You’re better than plastic, they were telling you, or, more accurately, you’re better than plastic that just looks like plastic. You’re not quite worth real wood, of course (who among us is?), but you’re worth taking the time to be deluded into thinking that you are, at least just a bit. For the wagons, there was another interesting discriminator of status when it came to wood paneling, and this was something that went across the Ford and Mercury wood-paneled wagon lineup. On Fords, the fake wood was bordered with more, paler fake wood, while on the Mercurys, the fake wood was bordered with chrome trim:

I’ve always found this to be a bit odd, as to my eyes, the light wood border just looks better, perhaps even a bit less fake. Still, I guess they had to do something, so thin chrome trim it was. There were also more sporty versions, and those interiors had less wood and more black, because black was kinda sporty and kinda European, which could be made synonymous with sporty. In fact, on the Bobcats that had sporty appearance packages, we see an interesting conflict at play, because a lot of the signifiers of class are inherently at odds with the easy signifiers of sportiness. Here, look at this Bobcat with the Sports Package Option:

The tall, chrome grille and the chrome bezels all kind of feel at odds with the stripes and blacked-out pillars of the Sports Package, don’t they? It’s like the car is trying to be two different things, and it’s confused. When the Bobcat and Pinto were re-designed in 1979, the Bobcat lost its distinctive tall hood and grille shape, but that did lend itself better to having its chrome blacked out and as a result, the car had much less of an identity crisis:

That’s very clearly more sporty-feeling, and a bit more modern, too. Unfortunately, this redesign also robbed the Bobcat of a lot of its visual distinctiveness compared to the Pinto. You can see up there the taillights are now redesigned, but no longer as bold and wide, and from the front the situation is just as bad:

Aside from the name and vertical instead of horizontal chrome grille slats, what’s the difference here, really? Is verticality enough of a signifier of status to justify the Bobcat’s existence? I’m not so sure it is. You don’t see too many Bobcats today even though a respectable 224,000 or so were made, and they’re not particularly in demand by collectors, even collectors who might want a Pinto. Still, I think a clean little Bobcat would be kind of a novel classic car to have today, even if it’s just a little rolling reminder of all those details that people once were told to consider “classy.” I think most people thought Cadillac, Lincoln, and Chrysler as luxury cars. The others were pretty much interchangable. I know Mercury was supposed to be over Ford, but when you were looking at used cars if it has automatic and A/C it was equipped, manual and no air, stripped. Maybe in the thirties when the brands were created there was more differentiation in the public eye. I don’t even know which is supposed to be better, Pontiac or Oldsmobile (both now dead). Buick was about the only brand that really had any cachet other than the top three American luxury brands already mentioned.